The Wright Brothers

Fifty-nine seconds. That was all it took to alter the course of human history as we know it. Of course, the years of work, of toil, of trial and error, starts and stops, of near-deadly mishaps and, eventually, of triumph that led up to that nearly one minute are often overshadowed by the simple action of thrust versus lift, of fifty-nine seconds of flight.

Too often does history remind us that Wilbur and Orville Wright took flight in their spartan air machine mere feet off the sandy soil of a bulbous hill in Kitty Hawk, along North Carolina’s Outer Banks, without recognizing the years these men, two self-taught engineers, took to get to that very history-changing moment.

High school dropouts, the Wright Brothers were natives of Dayton, Ohio who began their careers in the then-blossoming bicycle industry. After owning a sales and repair shop, the duo began building and selling their own bicycles via the Wright Cycle Company.

Their focus would soon shift, however, from ground to air. Interested by early advancements in human flight and galvanized by the death of early glider pioneer, the German aviator Otto Lilienthal, the Wright Brothers began experimenting with mechanical aeronautical engineering in late-1896.

Over the next half-decade, Wilbur and Orville explored the possibilities of manned flight and human control on their home-built gliders.

One of their most stunning and longstanding innovations involved the simple concept of how to turn their flying machines. While many of their contemporary aeronautical engineers thought of turning in the sky would be akin to turning on land -- that is, to simply point your nose left or right as you would a car -- the Wright Brothers conceptualized the idea of a bank and roll. In examining the flights of birds and by using their own backgrounds as bicycle builders, the duo surmised that a bank, in which the bird, the bicycle rider or, in their case, the pilot leaned into the turn, banking their outside edges toward the sky and rolling the body of their aircraft in the direction they wanted to go, would more effectively and efficiently turn an aircraft.

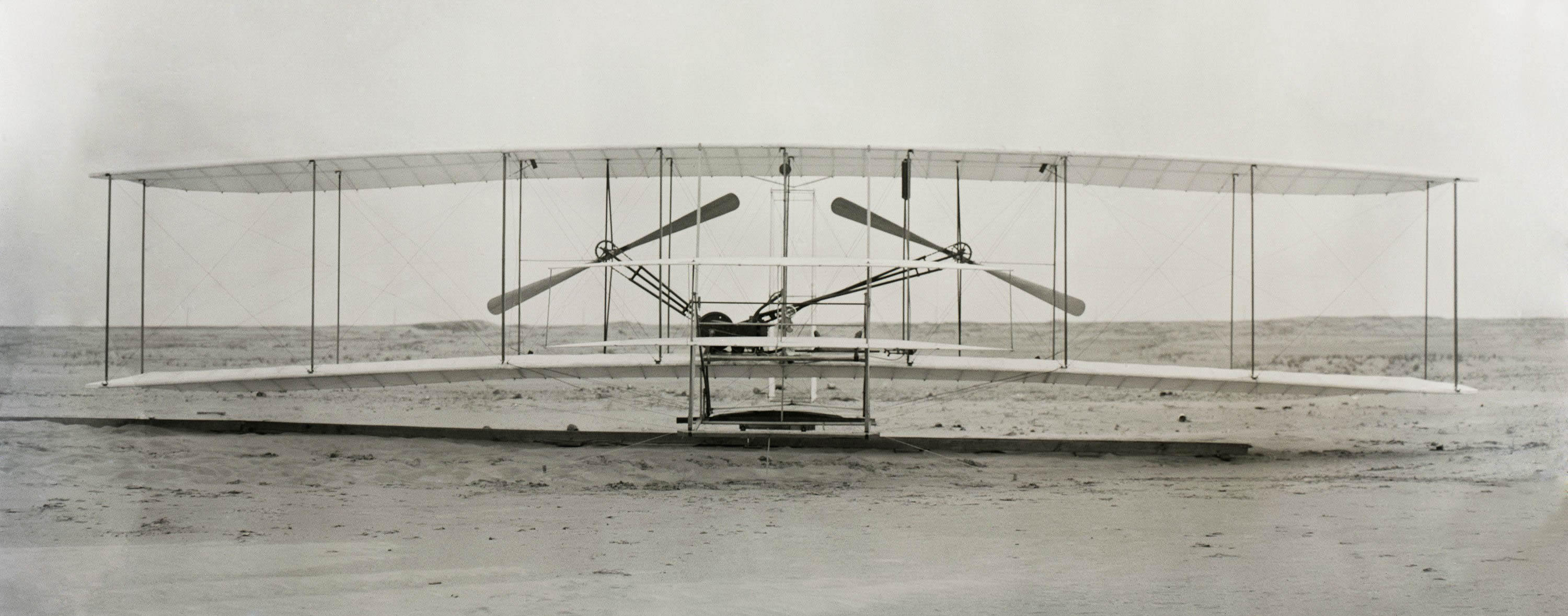

In mid-December 1903, after years of experimentation with stability control, lift, piloting mechanisms and basic aeronautics, and armed with a self-built engine (as no automobile manufacturer could provide a powerplant that was both light enough and powerful enough to provide the required thrust) the Wright Brothers took their first manned flight.

Their most famous flight, the one which occurred over those fifty-nine seconds, was actually their fourth of the day. Orville took the first flight, spanning twelve seconds and covering 120 feet. Wilbur manned the second, Orville the third, each of which went a bit further than the last. By the time Wilbur manned the aircraft for their fourth attempt, just around noon, the wind was perfect, taking him a then-miraculous 852 feet and eventually tumbling into the sand, breaking the frame of the front rudder beyond repair.

But history had already been made. Orville and Wilbur Wright had successfully piloted a powered aircraft over land, changing forever the course of human history.

It’s been almost a hundred and twenty years since the Wrights flew just twenty feet above Kitty Hawk’s sandy dunes. In the time since, the advancements in aeronautics would’ve left the brothers speechless. From transatlantic journeys to supersonic flight to sending humans to our moon, manned flight has traveled in leaps and bounds since 1903. But none of it would have ever happened without the persistence, the courage and the foresight of the two brothers, high school dropouts and self-taught engineers, who dreamed that they might one day take to the sky.