A Case for Slowing Down

I used to run too fast. My bi-weekly jog always—always—escalated into a Forrest-Gump-like pace. I’ve lived on a steady diet of Gym Jones, CrossFit, and SOFlete-style programming for the last decade, which has molded me into chronic go-hard. If I’m exercising, I prefer it to feel like a near-death experience. And because you’re on this site, I think we may have that in common. Don’t get me wrong; the occasional high-speed run is important. But redlining every cardio session is bad training. A weekly day or two of long-distance, low-intensity cardio work can not only improve your recovery and heart health, it can also take time off your faster runs and improve your lifts.

It works like this: Going hard improves your top-end fitness, ability to sustain high-intensity work, and the force with which your heart pumps blood. Going easier—a casual jog, slow rowing or swimming—helps you recover quicker, resets your central nervous system, and expands the chambers of your heart. The combo of the two results in your heart being able to pump more blood with more force.

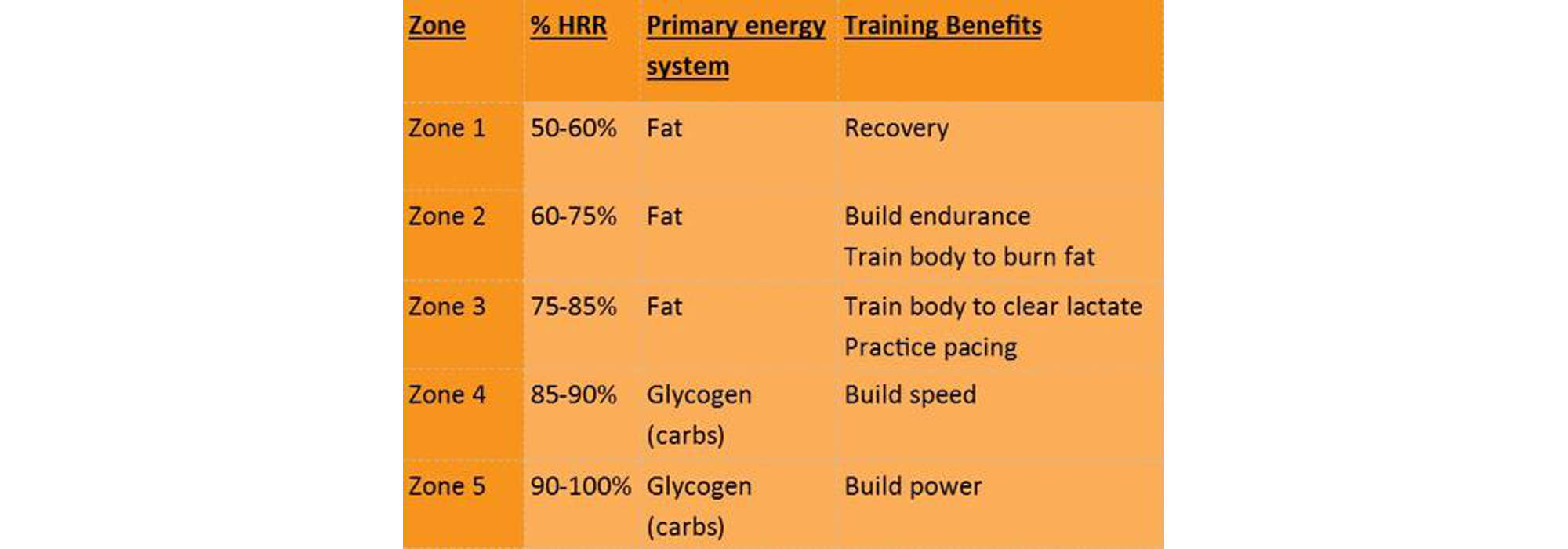

This “aerobic zone” is where your heart rate sits between roughly 60 an 70 percent of its max output. Not a data dork? This is a pace where you can hold a conversation while you exercise.

There’s plenty more info available about why sustained training in this zone is so important for everyone from operators, to big-four athletes, to CrossFit competitors, to dudes just trying to be harder to kill, such as myself. Problem is, exercising in this zone feels brain-numbingly easy. After just a few minutes your mind will drift, your conditioning will pick up, and your casual jog will devolve into a run, raising you into too high of a heart rate.

That’s where you enter what my friend Chris Frankel, an exercise physiologist with a Ph.D., calls “muddle in the middle.” This is a space where you’re not going hard enough for a top-end fitness effect, but too hard for a recovery and aerobic effect. It’s not useless work. But you’re also not cashing in on those aerobic benefits—and you may be impacting your recovery. (Side note: One huge benefit of zone-two training is that it’s particularly good for heart health. Heart Disease is the number one killer of Americans. In fact, if you’re non-military I’d argue more zone-two work is far more likely to help you avoid death than more gun drills.)

After years of screwing up my own zone-two work, I developed a few tricks to take it easy and keep my cardio laid back. See if they work for you.

Use a heart rate monitor (duh!)

Strap-based will always be more accurate than a monitor with a wrist tracker. Set it and go—all you have to do is look down at your wrist and make sure your heart rate is between 120 and 140 beats per minute. I’m a fan of everything Polar makes, especially M430. You can even set it to beep when you go outside the zone.

If you're needing a more rugged solution, Garmin's Fenix 3HR isn't their newest model, but it has served a lot of us well for many years, it's still competitive and durable at a really great price point. It has a wrist monitor and is compatible with strap monitors as well.

Time your breath

I learned this method from both Bud Coates, who wrote Running on Air. You basically do this: Breathe out for an odd number of strides, then breathe in for an even number of strides. For example, take three strides on the out breath, four on the in. Repeat throughout your entire run. This method is ideal for a couple reasons: It acts as a natural governor on your pace—you’re going too hard if you can’t sustain the breathing pattern—and it can reduce your injury risk, because your most impactful stride, your first stride on your out breath, occurs on a different leg each cycle.

You might need to use a heart rate monitor once or twice to calibrate this, but zone two is usually that three-on-the-out, four-on-the-in cycle. If that’s too fast, just add a breath to each stride.

Build a playlist

What kind of music do you play when you’re trying to set a new PR in the deadlift? Probably some gangster rap or death metal to match the intensity of the moment. The opposite should be true when you’re trying to turn down the intensity. It’ll work: Researchers say that athletes tend to pace their speed to the energy of the music their listening to. For recovery cardio, think along the lines of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue rather than AC/DC’s Back in Black. Here’s my Relaxed Training playlist, if you want a taste of what I’m talking about.

*Michael Easter is a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, a Contributing Writer at Men’s Health and Vice, and the Performance Plate Columnist at Outside magazine. He wrote The Maximus Body and lives on the edge of the desert. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter—@michael_easter—and check out his website: eastermichael.com